What’s the right approach to sensible environmental protection?

13 February 2019, by Stephanie Janssen

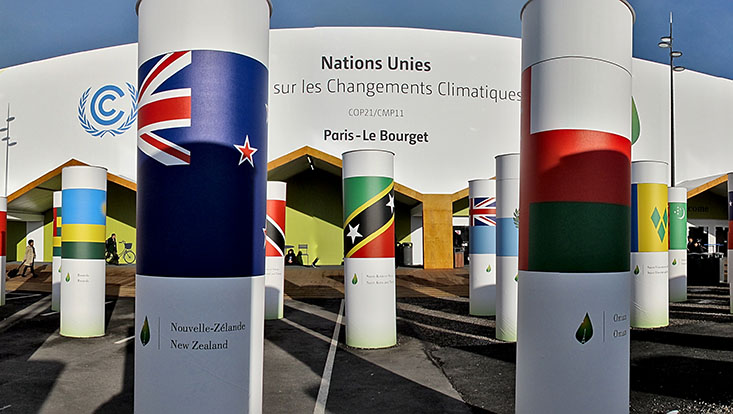

Photo: UHH/CEN/K.Jantke

Not the way it’s been handled so far, according to Dr. Kerstin Jantke, who claims there is no global strategy for protecting the right marine and land areas. In response, the environmental scientist in collaboration with researchers of the University of Queensland, Australia, has now developed a new software tool to make planning more efficient and help preserve biodiversity.

Ms. Jantke, the total area of protected zones around the globe has been increasing for decades. And it has been agreed that by 2020, ten percent of ocean and 17 percent of land areas will be protected. That goal has now largely been achieved. Is this a cause for celebration?

Yes, the protected areas are growing larger as 2020 draws closer. International agreements such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) and the Aichi Biodiversity Targets have definitely had an effect. But the figures only refer to the total area. If we take a closer look, the picture isn’t quite as rosy.

What’s wrong?

Current research indicates that a third of the areas are only sufficiently protected on paper. Either there are no local checks as to whether the protection regulations are being adhered to, or there are no regulations at all. We call such zones paper parks, and some of them are nothing but paper tigers.

You have also discovered that the protection zones themselves are not of the agreed-upon size – even though the area targets have been reached. What does that mean?

What matters most is which areas are protected. To conserve the variety, the biodiversity, of our planet, we need to protect a part of every ecosystem – from the Arctic, to the Tundra, to the Caribbean. To do so, the global land mass can be divided into 825 different ecoregions; the ocean is home to roughly 260 more. According to the agreement, ten percent of each of these regions should be protected. But this is largely ignored.

Isn’t that automatically the case if a country protects a sufficient area?

No. Marine protection in Australia is a good example: 53 unique marine ecoregions can be found around the continent. The country has designated 43 percent of its oceans as a huge network of protected zones, and as such has met the targets. However, our analysis shows that despite this, twelve of the ecoregions are not adequately protected and seven are not protected at all.

Why aren’t countries offering adequate protection?

They first look at which areas can be protected cheaply, without the population or the economy having to make any significant sacrifices. This leads to some countries protecting large areas of the same ecoregions and ignoring the others. At the same time, to date we haven’t had the proper tools to measure these areas easily. That’s why we’ve now developed a freely available software package to enable countries to assess their status themselves.

What can the software do?

The program determines what area of each ecoregion is protected, in order to identify gaps that would otherwise be difficult to recognize. Further, the total value for the “protection coverage” is particularly useful, since with a variety of ecoregions and several small protected areas, things can quickly become confusing. Our new parameter shows to what percent a given country’s targets – e.g. protecting ten percent of every ecoregion – have been met. This means that for the first time, we can create a clear and simple ranking list for countries or continents.

Is it really so important that every tiny ecoregion be preserved?

On our planet, there’s not a single ecosystem that is completely isolated; as such, we shouldn’t run the risk of destroying any of them. In addition, genetic diversity makes it easier for plants and animals to adjust to changing conditions. Climate change represents an especially rapid transformation in our habitat: the broader the spectrum within each species, the better that species will be able to adapt.

In 2020, new targets may be formulated under UN leadership in China. Which targets would you hope to see?

Quantifiable targets like concrete percentages are a good thing – but the numbers themselves have been too small. As a scientist, I would have to say that at least 30 percent of any given ecoregion has to be protected in order to ensure that endangered animals and plants survive – and to ensure they can continue performing important functions, like filtering the air and water, in the long term. That’s the kind of target I’d like to see.

Scientific paper:

Metrics for evaluating representation target achievement in protected area networks (2018): Jantke K et al. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/ddi.12853

Poor ecological representation by an expensive reserve system: Evaluating 35 years of marine protected area expansion (2018): Jantke K et al. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/conl.12584

Contact:

Dr. Kerstin Jantke

Centrum für Erdsystemforschung und Nachhaltigkeit (CEN)

Universität Hamburg

E-Mail: kerstin.jantke@uni-hamburg.de

Tel.: +49 40 42838 2147