35 years of marine conservation: the lack of a strategy increases the need for protected areas

26 June 2018, by Stephanie Janssen

Photo: UHH/CEN/K. Jantke

Although more than 16 percent of all national waters are now protected, many ecoregions and countries are not included. The current reserve system is just as expensive as it is inefficient, as Dr. Kerstin Jantke and her team show in a study recently released by Universität Hamburg’s Center for Earth System Research and Sustainability. If strategic planning had been implemented from the outset, every ecoregion could now enjoy suitable protection.

International agreements like the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the United Nations (UN) Aichi Biodiversity Targets specify that, by 2020, at least ten percent of the world’s coasts and oceans are to be protected areas – and today, with ca. 16.8 percent, that goal has already been reached. Further, the areas protected weren’t chosen at random: a further specification is that all marine habitats be included, in an effort to stem the loss of biodiversity around the globe.

Together with experts from the University of Queensland, Australia, the environmental researcher Kerstin Jantke analyzed marine protected areas, from their origins in 1982 to 2016. In this regard the team only examined national waters (39 percent of the total ocean), as international waters have proven difficult to protect. These national waters consist of 258 ecoregions – comparatively large areas that can be geographically demarcated on the basis of their local species and environmental conditions. For each region, ten percent should be protected. Yet the study shows that more than half of the ecoregions (157) are not sufficiently protected; ten of them aren’t protected at all.

(©K. Jantke - high resolution, see below)

It is particularly important that these areas be strategically selected in the future. The team compared their size from year to year, and simulated an optimal expansion of protected areas. If tactical planning had begun in 1982, only 10.3 percent of the national waters would have sufficed; in 2011, 13 percent would have been enough to provide the agreed-upon ten percent protection for all ecoregions. As such, the goal could have been long-since reached and the follow-up costs, e.g. those resulting from limitations on fishing, would have been far lower.

“The individual countries need to proceed systematically and pursue strategic collaborations. Only then can we address the massive gaps in the current system,” says Jantke. “But in most cases, national and commercial interests are what come first. In the future, first of all new protected areas need to be established in the less-protected ecoregions.”

In 2020, new nature conservation goals will be negotiated in China, under the auspices of the UN. Many experts believe the future of a given ecoregion can only be safeguarded if at least 30 percent of its area enjoys protected status. As Jantke explains, “I’m in favor of protecting additional areas. After all, biodiversity is essential to our livelihood. Another aspect to consider is that, even if these areas aren’t completely immune to climate change, their protected status improves their chances of adapting to new climatic conditions.” The current study lays the groundwork for a future approach to marine conservation that is more systematic.

Original article: Jantke K., Jones K.R., Allan J.R., Chauvenet A.L.M., Watson J.E.M., Possingham H.P. (2018): Poor ecological representation by an expensive reserve system: evaluating 35 years of marine protected area expansion. Conservation Letters, DOI: 10.1111/conl.12584

https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12584

Images for download:

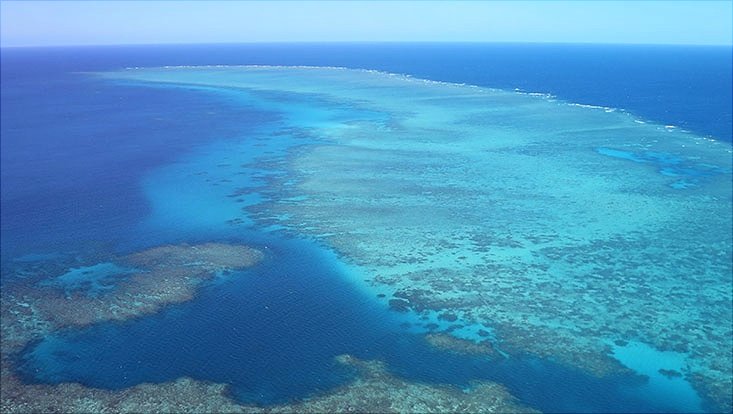

Photo: Great Barrier Reef ©UHH/CEN/K.Jantke

The Great Barrier Reef in Australia, one of the 258 marine ecoregions examined

Map: Protection of ecoregions ©K.Jantke

The chart shows the ecoregions in 2016, light grey = 10% or more protected, dark grey = less than 10% protected, red = no protection. Ecoregions not sufficiently protected (dark grey) are mostly found in the marine areas of densely populated countries.

Contact:

Dr. Kerstin Jantke

Center for Earth System Sciences and Sustainability (CEN)

Universität Hamburg

E-Mail: kerstin.jantke"AT"uni-hamburg.de

Phone: +49 40 42838 2147

Stephanie Janssen

Outreach CliSAP/CEN

Center for Earth System Sciences and Sustainability (CEN)

Universität Hamburg

E-Mail: stephanie.janssen"AT"uni-hamburg.de

Phone: +49 40 42838 7596